- The Heinrich Simon Papers

- /

The Digital Edition of the Heinrich Simon Papers

The Digital Edition of the Heinrich Simon Papers

The vast majority of the items in the Heinrich Simon Papers were written in Kurrentschrift, a hand notoriously challenging for present-day readers. Indeed, a note attached to the papers in Birmingham describes them simply as indecipherable. Transcription was therefore of vital importance if the rich material were to be made accessible for research. That work was led by Eva-Maria Broomer, who collaborated with Stephen Parker on editorial work. At present, the Digital Edition comprises some 600 items, spanning the years 1807-1827, which chronicle the early life of Heinrich Simon within the rich fabric of the Breslau Simons' family history. The items are presented in chronological order in six parts, each introduced by a short summary of content. The items in the edition are accompanied by transcriptions and underpinned by a scholarly apparatus, including selected translations, which is designed to facilitate further research.

Part One

The Simons during the French Occupation of Breslau

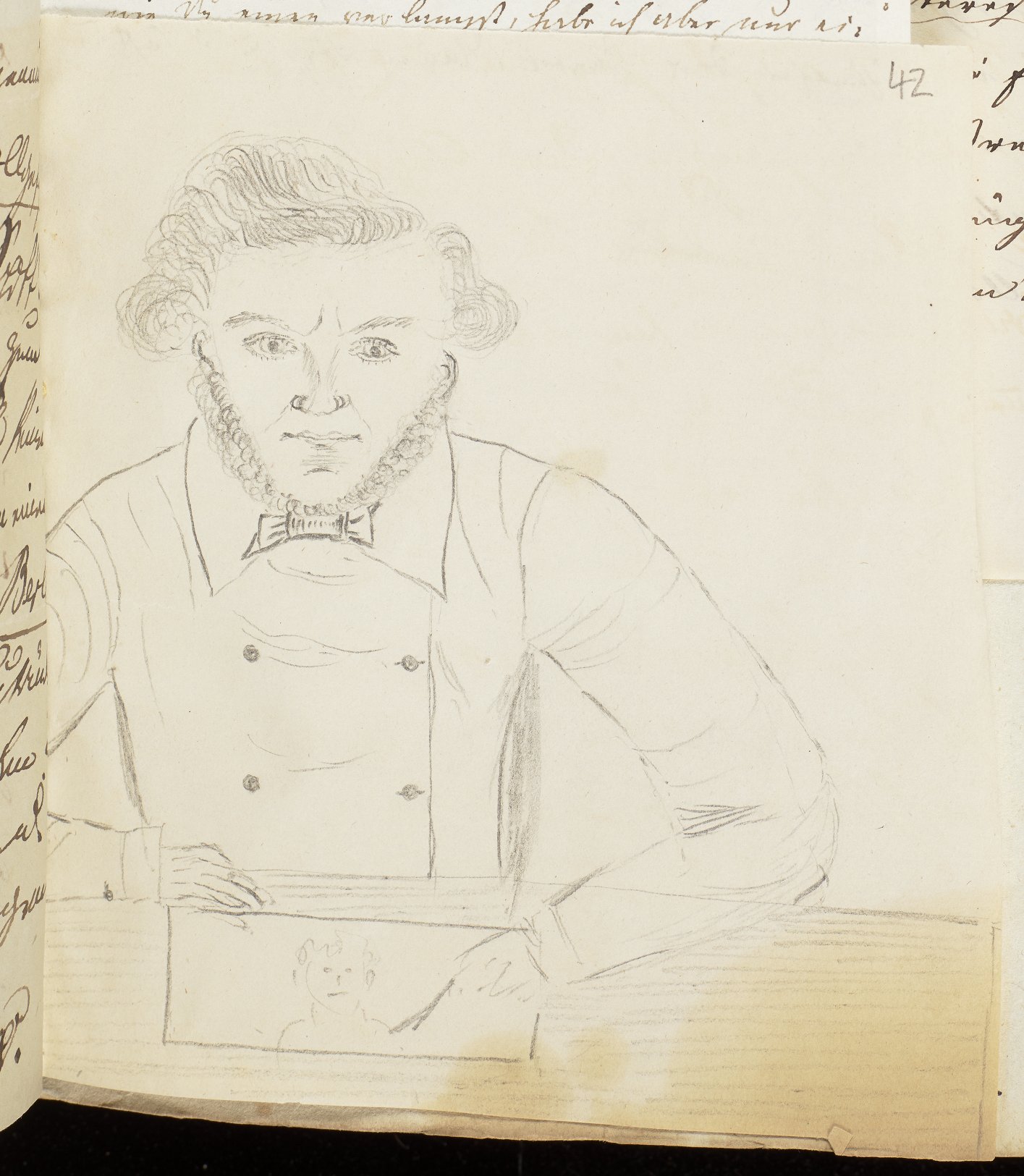

The Digital Edition of the Heinrich Simon Papers opens in January 1807 with the Breslau merchant Herrmann Simon’s dramatic account, sent to his brother Heinrich Simon the Elder a trainee lawyer in Berlin, of Jérôme Bonaparte’s siege and occupation of Breslau. In their subsequent correspondence Herrmann conveys to his brother not only his relief that his growing family and their relatives have survived the bombardment of the city but also their subsequent exposure to the daily depredations of the occupation. In addition to the insatiable demands of the French garrison, Napoleon’s military authorities imposed a crippling war indemnity upon Prussia. Those who, like the Simons, could pay were required repeatedly to provide funds, together with clothing and horses for the Grande Armée’s march to the East. Along with the confiscation of goods and their theft in transit, these losses drastically reduced the Simons’ fortune which their father Hirsch, a ‘generally privileged’ Jewish merchant, had amassed during the Seven Years’ War and after as a supplier of coins to the Prussian monarch, Frederick the Great. Herrmann’s correspondence with his brother captures equally dramatically the crucial role that Breslau played in the gathering of forces for that watershed moment in the Coalition Wars, the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, when Napoleon’s armies were defeated and expelled from the German lands. The Simons’ younger brothers, Otto and Ludwig, were both killed in combat while serving in the Silesian Army commanded by General Gebhard Blücher, the Duke of Wellington’s ally in 1815 at Waterloo. Herrmann Simon’s eldest son Heinrich Simon the Younger, born in 1805 when the family also converted to Christianity, would always revere his uncles for their sacrifice in the Prussian patriotic cause. From an early age, Heinrich’s own energy and strength stood out. Herrmann Simon told his brother that, however difficult Heinrich was proving to be, he was his favourite child. In fact, he was so headstrong and so fixed in his views that he could scarcely be shifted from them and was actually so disruptive that when he was just four the Simons asked the clergyman and pedagogue Friedrich August Nösselt to take him into his care. Heinrich remained with Nösselt until the Simons employed Eduard Kaiser as a private tutor for Heinrich and his two elder sisters Emilie and Julie when Heinrich was six.

Part Two

The Breslau Simons’ Business Failure

In his correspondence with his brother Heinrich Simon the Elder, Herrmann Simon describes the swift upturn of the family business after the expulsion of Bonaparte’s armies. Hence the Breslau Simons resumed their patrician lifestyle, Herrmann taking his son Heinrich Simon the Younger to Cudowa, one of Silesia’s oldest and most prestigious spas, in the summer of 1814. Other surviving documents include evaluations of the children’s academic progress by their tutor Eduard Kaiser. Meanwhile, Heinrich Simon the Elder’s legal career blossomed in Berlin. Chancellor Hardenberg selected him as a member of the Royal Unmediated Justice Commission [Königliche Immediat-Justiz-Kommission] for the Rhineland Provinces, which Prussia had acquired at the Congress of Vienna. Heinrich Simon played an outstanding, reformist role in the work of the Commission, first in Cologne, then back in Berlin. The Breslau Simons’ resumption of their patrician lifestyle proved to be short-lived: not only had Napoleon’s rapacity caused incalculable, long-term damage to the European economy; in early 1817 the very foundation of the Simons’ wealth and privilege was swept away. What Herrmann Simon and others experienced so sharply in Breslau as the result of bad credit was part of a crisis gripping Europe and much of the world after the failure of the grain and potato harvests in 1816, the ‘year without a summer’. As we now know, the eruption of Mount Tambora in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) in April 1815 triggered the calamitous sequence of events. Herrmann Simon wound up the family business and found a position in Breslau as a broker for banking and exchange. Henceforth, all the children were educated in public institutions, in Heinrich’s case initially Breslau’s Königliches Friedrichs-Gymnasium [King Friedrich Grammar School]. In the first surviving letter in his hand, the eleven-year-old Heinrich describes to his former tutor Kaiser a violent confrontation between the Breslau authorities and a group of citizens (which was, in fact, symptomatic of the widespread social unrest in the fragile post-1815 order). Heinrich’s weekly reports from his new school have also survived: they began well enough but his diligence lapsed in the autumn when his elder sister fell seriously ill. Emilie Simon died on Christmas Eve 1817. Heinrich’s lack of diligence would be a constant worry for his parents in the years to come.

Part Three

Heinrich Simon’s Schooling in Brieg

Heinrich Simon the Younger’s lack of diligence prompted his parents Herrmann and Minna to send him to board at the Royal Grammar School [Königliches Gymnasium] in Brieg in 1819 under the guidance of the headmaster Friedrich Schmieder, a liberal like Herrmann Simon. The homesick Heinrich Simon was deeply unhappy at Brieg, The rich records from that time onwards, including not only family correspondence but also school reports, exercise books and notebooks, some diaries and many calendar notes, offer a privileged insight into Heinrich’s activities, interactions and developing character traits, particularly his assertiveness, outspokenness and sense of rectitude. Within the confines of the all-male boarding school, these things made for often difficult relations with teachers and fellow pupils. School reports were generally no more than satisfactory. On one occasion when the boy challenged the head’s authority he was dismissed from the boarding house and only permitted to return after his father’s intervention. His parents repeatedly urged greater diligence and self-discipline to correct flaws. By his final school year, Heinrich Simon managed to muster his considerable powers so successfully that in his Abitur he secured the highest award that the school could give. Heinrich Simon’s turbulent school years took place against a backcloth of continuing social and political unrest, notably the assassination of the conservative propagandist August von Kotzebue by Karl Sand, a partisan Burschenschafter [member of a student society] and supporter of the pan-German cause. Heinrich Simon’s correspondence with his sister Julie includes reflection upon Sand’s execution. The Prussian authorities, like those in other German states, responded to dissent and opposition with the draconian measures of the Carlsbad Decrees, which, among other things, banned student societies and imposed political censorship on university teachers and the press. Heinrich Simon’s letters home discuss the measures that Schmieder was required to take in the school, and Simon’s diary reveals that he established contact with the student leader Gustav Adolph Haacke, who had founded the Breslau Armenia Burschenschaft.

Part Four

Heinrich Simon as a Student in Berlin

Heinrich Simon’s letters, drafts and diaries represent a rich, increasingly sophisticated source for the understanding of his life as a student in Berlin. He found the Prussian capital immensely stimulating. Its centre bore the magnificent, neo-classical imprint of the great architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel ,whose work did so much to reshape the city after the French occupation. Herrmann Simon introduced his son to the family’s merchant and banking friends, the Blochs, whose salon Heinrich Simon the Younger would attend. Like the Simons, the Blochs were converted Jews with close connections to the Prussian establishment. Similarly, Heinrich Simon the Elder introduced his nephew to his circle of prominent politicians, academics and public servants, among them the minister Karl Friedrich von Beyme, the lawyer Friedrich Carl von Savigny and the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher. Heinrich Simon the Younger launched himself into the Berlin social world. Along with the Charlottenburg Theatre and the Royal Theatre on the Gendarmenmarkt, the new Königsstädtische Theater, designed to emulate Vienna’s popular culture of commercial theatre, was a regular venue. There was also the matter of matriculation, during which Heinrich Simon was required to sign an extract from the Carlsbad Decrees, pledging that he would not join a student society. There are detailed accounts of his lectures, lodgings and the restaurants Heinrich frequented, his trips out friends and encounters with the royal family in galleries, at balls and whilst sleigh-riding with other students in the Tiergarten. Initial fascination with the Hohenzollerns gave way to a much more critical attitude, often expressed in terms of their bad taste. Social life continued to figure more prominently than his application to his studies, not least during a quite long visit from his rich uncle Jakob Lewald. For Heinrich Simon, the downside of Berlin was that its representative and political functions left little room for the student life of traditional German university towns like Göttingen, Halle and Heidelberg. Although student societies had ceased to exist as formal entities following serial repression, he became involved informally. That included a quite alarming number of challenges to and from fellow students to fight duels, one of which issued in a fencing duel. He also took part in the drinking rituals that were part of the lifestyle but also succumbed to illness on more than one occasion, in a pattern of ill-health that would cast a shadow over his life.

Part Five

The Wandering Student

The importance which Heinrich Simon attached to his month-long, late-summer hiking holiday with his university friends is attested in his 114-page travel diary, the letters that he wrote to his family from various stopping-off points and an edited version of the diary for them. As might be expected of the high-spirited, adventurous Heinrich, he did not divulge to his family the entirety of what he and his friends had been getting up to. They travelled by coach from Berlin to Potsdam, viewing the Marble Palace, then on to Wittenberg, viewing the spots where the revered Luther had lived and worked. From there they walked to Wörlitz, where they visited the famous park, the Gothic House and the castle, carrying on to Dresden via Dessau, Torgau and Meissen. Heinrich was very taken by Dresden’s fine architecture and sampled its art, music and theatre. They then hiked along the Elbe through Saxon Switzerland towards the Bohemian border, taking in its rock formations, castles and stunning landscapes, not lease the steepling Uttewalder Grund, the awesome splendour of which Caspar David Friedrich immortalised that same year in his glorious painting. In the evenings they drank heartily in local inns and returned to Dresden by boat. Heinrich visited the Green Vault but its flamboyant excess, like the Marble Palace, did not suit his taste. Dresden’s old masters were much more to his liking, particularly Raphael’s Sistine Madonna, as were the casts in the Mengs Collection. Heinrich and his friends travelled on by coach to Leipzig, then Halle and the Harz mountains, visiting Eisleben and Mansfeld, before journeying further through the Harz and climbing the Brocken. The diary breaks off at this point though the journey continued to Göttingen, Kassel, Magdeburg and then back to Berlin, attested in letters from Heinrich Simon to his family, in which he confessed to spending far more than intended. Towards the end of his journey he also acknowledges to his family that the life of the vagabond is not for him! He then embarked on his third semester in Berlin, promising to be more diligent but once more becoming caught up in altercations threatening to escalate into duels. Letters home from this time reveal Heinrich Simon’s belief that his correspondence was being read by the authorities in their surveillance of student ‘demagogues’. Heinrich Simon and his father finally agreed - after much disagreement, particularly with Uncle Heinrich - that the family’s financial situation was such that he would return home to Breslau for two semesters rather than going to Heidelberg.

Part Six

Heinrich Simon as a Student in Breslau

Following Heinrich Simon’s departure for Breslau on 1 April 1826, conversation within the family replaced the extensive correspondence from the time in Berlin. Hence, a more fragmented record of discussions between Heinrich Simon and his family exists for the following months and we know a little less about his everyday life. Only individual pieces of correspondence and Heinrich’s occasional notes remain, except for a calendar page for each month in 1826, containing information such as his registration at Breslau University on 8 April. We have a record of Heinrich Simon’s critical reflections on the duelling culture that he and his friends had become caught up in through student life. Simon goes so far as to describe duelling with pistols as the most ridiculous and scandalous thing. Despite this clear acknowledgement, he and his friends nonetheless became embroiled repeatedly in the rituals surrounding duelling simply because they were so much part of the student culture that they embraced. That said, the aim was now for Heinrich to complete his studies in just a year. Despite further illness, he worked hard for his exams at the end of the semester in early 1827, revising regularly with Ohlen, Prittwitz and other friends. At a family event, Heinrich Simon also got to know Ludwig von Rönne, a trainee lawyer in Breslau. Just a few months older than Simon, Rönne, a reform-minded liberal, would rapidly become a close and influential friend. In time, he would also become a close collaborator in their co-authorship of major legal texts, following in the footsteps of Uncle Heinrich in codifying fragmented Prussian law. Rönne’s influence is apparent in new orientations in Heinrich Simon’s reading from this time, which included Friedrich Buchholz‘s Neue Monatsschrift für Deutschland. The radical Buchholz used his journal as a platform for new thnking about social and economic forces, in particular the introduction to Germany of the French philosopher Henri de Saint-Simon’s early socialist thought and later the sociological and positivist writings of Auguste Comte. Buchholz also championed the English constitutional tradition and Adam Smith’s scientific method. The overarching message was that the German lands had much to learn from France and Britain if they were to achieve the modernisation acutely necessary for the emulation of their near neighbours. Rönne, who was engaged to the Brandenburg court Director Kuhlmeyer’s daughter, advised Simon to go to Brandenburg to take the first professional law exam for admission to a traineeship. Heinrich Simon the Elder then wrote to Kuhlmeyer on his nephew’s behalf about a traineeship at Brandenburg, which was confirmed for October. In September Heinrich Simon the Younger took the first professional exam in Berlin and passed with flying colours.